“The power of ‘the Eye of the Heart,’ which produces insight, is vastly superior to the power of thought, which produces opinions” (E.F. Schumach)

“’Cause hearts are the easiest things you could break” (“Some Candy Talking”, Jesus & Mary Chain)

“Poetry is like the human heartbeat. It belongs to everyone” (Imtiaz Dharker)

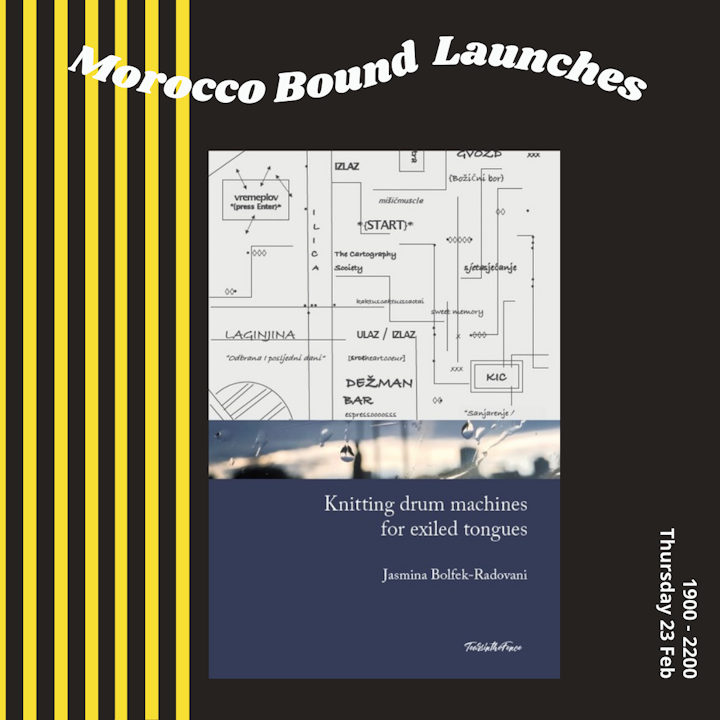

The meeting (of) minds. In June last year I was invited by Terry Lamb to give a performance of my multilingual poetry (in English, French and Croatian) at the first University of Westminster festival on global culture “World in Westminster”, 15-17 March 2022, celebrating cultural and linguistic diversity. We had discussed the idea of the performance back in 2019 but were unable to develop it due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Terry is a fine scholar and his commitment to language teaching and learning, as well a s to multilingualism are exceptional; I was both honoured and extremely pleased to be able to collaborate with him on the festival and to be able to bring my performance to the stage as an alumna PhD student of Westminster University.

Heart monologues / Les monologues du coeur / Monolozi srca. When presented with an opportunity to give a live performance after two and a half years in lockdown, I immediately thought of my multilingual poetry sequence “Heartbeat monologues” (HM). I imagined it as a multisensory poetry recital incorporating elements of live music performance, sound, and live and recorded voices. I had just finished rewriting HM after having done some important work on it as part of my one-to-one mentoring work and summer workshop with poet, artist, and writer, Caroline Bergvall. This latest reworking of HM coincided with Terry’s invitation, which was perfect timing.

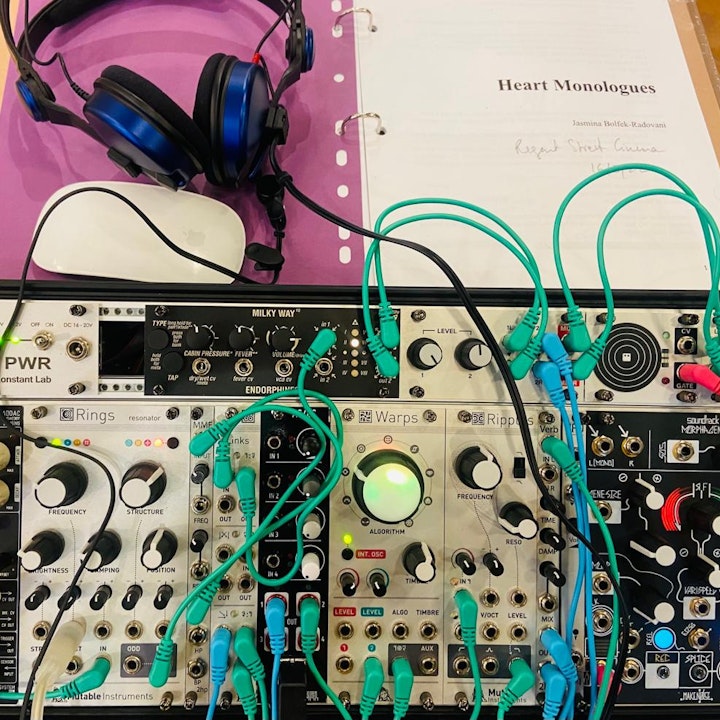

I want to say here that Heart monologues (HM) would not be the success it has been without Atau Tanaka’s and Delphine Salkin’s unique artistic input, and their dedication and expertise, the contributions made by Robert Šantek and Bridget Knapper, permanent members of my multilingual poetry Unbound project, and the voices by Daniel Loayza and Emma Macpherson, the pre-recorded readers, as well as the voices of so many others that came to life in Delphine’s audio piece “HeartCoeurSrce”. Last, but not least, Jonathan Pigrem, sound technician from the Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary, Martin Delaney, free-lance photographer and musician, Richard Woodford, Regents Street Cinema technician, and Ying Man, Regents Street Cinema Manager, all contributed to the success of HM by bringing their enthusiasm and expertise to the HM project.

Heartbeat matters. I have known Atau Tanaka professionally for several years now and I have the greatest respect for both his cutting-edge scientific research and his avantgarde performance work. Atau’s “Heart Beat Monitor” is a track from the CD, Biorhythms (Caipirinha Music, 2001). It used a stethoscope to record the heartbeat and has been mixed and processed in an analogue electronic music studio to create hypnotic polyrhythms. I heard “Heart Beat Monitor” some years ago almost by pure chance; my first thought back then was that it would work perfectly with the HM poems I had just finished writing; however, I was not sure how to take the idea of a collaboration further, nor what form it would take; I let this feeling sit with me thinking there would come an opportunity at some point in the future to get in touch with Atau. When I finally invited him to collaborate on HM and he agreed, I knew this was a very good sign.

“Faites que le rêve dévore votre vie afin que la vie ne dévore pas votre rêve”. After my preliminary chat with Atau at the Mughead Coffee in New Cross in October last year, I started thinking about the artistic direction of the performance and how I would achieve a sonic integration of my multilingual poetry with music, sound and voice. I knew that I did not have the necessary experience to put such as complex and multidimensional piece on stage; so, I reached out to Delphine Salkin, a Belgian-born theatre director, actress, sound artist and author currently living in Paris, and my best and oldest friend. I know Delphine since we were 12 years old and when I was living in Brussels with my family; we were spending a lot of time together daydreaming as teenagers and on one occasion she left me a note: “Faites que le rêve dévore votre vie afin que la vie ne dévore pas votre rêve / / “Let your dream devour your life, not your life devour your dream”, a quote from the Little Prince that stayed with me until the present day. Delphine’s artistic work on the human voice in performance, and her own very personal journey as an artist and woman who lost (literally) and recovered her own voice, an experience narrated in her autobiographical theatre piece “Interieur Voix” (2015), made her the perfect fit for HM. When I asked Delphine whether she would be free to collaborate with me and she accepted, I knew everything was falling into place.

“I am muscle, vivant souvenir”. Whilst the heartbeat sounds of “Heart Beat Monitor” introduced HM in poem 1, HM’s centre piece was Atau’s electronic music piece “Myogram” (Meta Gesture music, 2017) performed live; slowly entering the scene between poem 7 and 8, it continued throughout the second part of the HM recital including poem 9 with its opening line “I am muscle…” and intermittent play during poems 10, 11 and 12. As Atau explains: “Myogram” is a concert work for performer and the Myo bio-electrical interface as musical instrument. The sensors capture electromyogram (EMG) signals reflecting muscle tension. The system renders as musical instrument the performer’s own body, allowing him to articulate sound through concentrated gesture. A direct sonification of muscle activity where we hear the neuron impulses of muscle exertion as data. Throughout the piece, the raw data is first heard, then filtered, then excite resonators and filters.” Interwoven with Atau’s electronic music were the verses of HM live poetry read on stage by three live readers (Bridget, Robert, myself), and the two pre-recorded voices (Emma, Daniel). The pre-recorded poetry verses and Atau’s music were mixed on his Mackie mixer and a stereo signal was sent to the front-of-house. The three live readers used wireless Sennheiser mics, and all this was mixed by our sound technician, Jonathan. After more than twenty years of practicing and performing his body and gesture work, there is no doubt that Atau has become a virtuoso at it; yet, he remains very modest about his art.

Multilingual heart, multilingual voice(s). After doing a summary bibliographic review and speaking to an expert in theatre studies at Queen Mary University of London, I realised that the concept of multilingual voice was explored very little – if not at all – in theatre and voice studies. In HM, I wanted to explore the multilingual voice and its relation to the body through textual, sonic and musical expression. The public was invited to immerse her/himself in the different language sounds through the sonic and visual correspondences of the three tongues; I believe this approach to writing and performance allows the reader / listener to experience the multilingual poems without necessary knowledge of the three languages. The theme of the multilingual heart and the question of which languages the “heartsrcecoeur” speaks lie at the centre of HM; the heart is “monologuing” through a change of first, second and third-person narratives as a physical, poetic and philosophical entity. In the last two poems of the sequence (12 and 13) references are made to music research in heart arrhythmia and musical patterns, mixed with somewhat recent medical experiences. The final poem, poem 13 in which the heartbeats of “Heart Beat Monitor” return to the scene, is my poetic statement in which I fully apply the multilingual poetry method.

When trying to conceptualise my own ideas, the first question I asked myself was what does it mean to have a multilingual voice? Where in my body are the different languages I speak located? And more generally, what are the public’s expectations and perceptions of multilinguality? I cannot entirely tell how successful I was in treating these complex questions in the HM performance, yet there is no doubt that the poems in HM spoken out loud gained a quality that transcends any language, something that I believe was achieved through the sonic integration of sound, music and voice, and is the direct result of the collaborative artistic process we undertook as a group. Delphine’s sound piece “Heart Coeur Srce” played between poems 11 and 12 in which the sober notes of Pascal Salkin’s musical score are set against the voices of people (based on thirty different recordings) saying the word ‘heart’ in twenty-nine different languages is a celebration of, an ode to multilingual voice.

Artistic practice and collaboration. As a multilingual poet interested in collaborative practice and interdisciplinary work my experience so far has been that still exists a view prevalent in the poetry establishment in the UK, and among the poets themselves, that we as poets are expected primarily to work in solitude; solitary work is valued positively as being one of the distinctive traits that defines us; at the same time, these perpetuating views and conditions create a space(s) within which we primarily compete against each other. Luckily, the perceptions and the ideal of the solitary artist have begun to shift in all areas (see, for example, the 2019 Turner Prize that was for the first time ever awarded to a collective of artists, rather than one individual artist). It is true that the artistic creative process in collaborative work can be confusing, messy, unpredictable, and authorship can be difficult to assign. During an interdisciplinary collaboration, we are constantly being confronted with the question of what it is we as artists are willing to concede to give space for other possible modes of expressions to develop; yet, we learn also how to free ourselves up from our own artistic egos. We learn to negotiate our own identity, views, ideas as artists in relation to other existing identities and practices of the other artists we collaborate with. As Bridget, HM reader and group member, observes about HM: “What was noticeable [in the HM collaboration] was the harmonious, egalitarian nature of the group. There was a total absence of competition between the participants, no hierarchy, no directing leader. The author and director held their knowledge and competences lightly, creating a space for us all to navigate the text, the sound, the space.”

Since I became involved in interdisciplinary artistic collaborations through my multilingual poetry performances (I use the word performance here in the broadest of senses), I realised that mutual trust is one of the most important ingredients (if not the most important one) that defines whether such a collaboration fails or succeeds. The second most important ingredient is the right chemistry between the collaborators. Finally, the third one is the ability to trust the creative process, to “let go”. It is true that each collaboration is different, and that each participant has their own views about what makes a successful collaboration; it would therefore be wrong for me to assume we all share the same ideas and goals; however, it is safe to say that all successful collaborations (artistic or other types) invite a specific type of listening, quality of dialogue.

Collaboration and the practice of listening. Having attended a couple of Caroline’s collaborative practice workshops – most recently the 7-week “Practice conversations” course last summer with nine other artists, (as part of the newly founded Solitary + Solidary Arts Lab) – one of the things I learned is there is both an interdependency and a subtle balance between solitary and solidary artistic practice; an ecological equilibrium. In the messiness of today’s world, a solitary artistic mode of working can no longer function fully without the solidary mode, and the other way around. Embracing collaborative work as a method for the development of one’s own artistic practice not only enriches one’s own development; it also enables the community and work of other artists through the range of active listening practices; listening can become a key element of artistic practice, a “part of a two-way dialogue”, an “action” that leads to change (Farinati & Firth, 2017). It takes heart, openness, and courage to show our own vulnerability as artists before we are ready to embark on any kind of collaborative artistic voyage

A few final words.... The work on HM coincided with the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February. In the first days of the invasion, my memories, and images of the war in ex-Yugoslavia rushed back. I was stunned, speechless, incapable of articulating my own feelings, ideas; the horror of war is unfolding daily in front of our eyes more than 100 days later; so close to the heart of Europe; only three and half hours from London. In that context, any gesture, however small, counts. For me, HM and the collective sound piece “HeartCoeurSrce” represent that very small, but necessary gesture. To have heartcoeursrce. To have courage.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the Centre for Poetry, Queen Mary University of London, and the University of Westminster for co-funding Heart Monologues, 16 March 2022, Regent Street Cinema, University of London (Part of “World in Westminster” Festival, 15-17 March 2022). I also wish to thank the Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary, for their continued support.

References:

Materials from Heart monologues:

Bolfek-Radovani, Jasmina, Heart monologues (2m 47s), 2022, Youtube.

Bolfek-Radovani, Jasmina, Heart monologues (33 m), full audio recording, 16 March 2022, Regent Street Cinema, London, Soundcloud (recorded by Richard Woolford at the Regent Street Cinema, 16 March 2022). Bolfek-Radovani, Jasmina, Heart monologues, moving poster, 2022, Vimeo.

Salkin, Delphine (1m19s), Heart Coeur Srce, Soundcloud.

Tanaka, Atau, “Myogram”, Meta Gesture, 2017, Youtube

Tanaka, Atau, “Heart Beat Monitor”, Biorhythms, 2000, Youtube.

Related references:

Bolfek-Radovani, from Heart monologues: 1. & 3., The Fortnightly Review, January 2022.

Cavanero, Adriana, Towards a Philopsophy of Vocal Expression, Standford: Standford University Press, 2005. Farinati, Lucia & Firth, Claudia, The Force of Listening, New York: Errant Bodies Press, 2017.

Inchley, Maggie, Voice and New Writing, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Konstantinos, Thomaidis, Theatre and Voice, Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2017.

Salkin, Delphine, “Interieur Voix”, (first created in December 2015) Rideau de Bruxelles, December 2019 (With and by Delphine Salkin, Pierre Sartenaer, Raymond Delpierre, and Isabelle Dumont).

Practice Conversations, seven-week summer course led by Caroline Bergvall, 17 June – 29 July 2021, Solitary + Solidary Arts Lab.

Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani 29th June 2022, Tears in the Fence, summer 2022.