This essay was published in Balkan Poetry Today, February 2018.

(written by Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani Mina Ray)

I don’t think that one can be a bilingual poet. I don’t know of any case in which a man wrote great or even fine poems equally well in two languages. I think one language must be the one you express yourself in, in poetry, and you’ve got to give up the other for that purpose. (1)

For a very long time, I could not choose my language of writing. I had Croatian, French and, later, English at my disposal as writing tools, however, choosing one language for me always meant sacrificing my other languages, other cultures, other identities, other parts of Self. I don’t want to sound complacent; my experience is by no means exceptional. The question of language choice and/or language loss has been and still is a recurring one for many writers who have either inherited or have come into a prolonged contact with more than one culture / language / identity. Much later, I came to realize that the problem of language choice is a false problem for me as a writer. It would therefore be more true to say that for a very long time I thought I had to choose a language of writing. As, although I was not explicitly forced to think that way, everything around me led me to believe that I had to do so. I felt compelled to choose one language; the monolingual was, and still is, the standard, the norm, the “default” option.

So, I tried, and tried again to write in one language, and I failed, and failed again; I felt that when I was writing in only one of my languages I was always losing ‘something’. That “something”, I came to realize this later, is made up not only of notions and concepts, but also of sounds, images, as well as olfactory, emotional, cognitive, pragmatic and kinetic resonances of the words and the worlds I live in. Each of my languages has its own archeology; one of them contains my sensory and sensual memories, the other inhabits my thoughts, my Self, my consciousness, the third has primarily cultural resonances for me that I identify myself strongly with. Only after I decided that I would not or did not have to choose a language, did I arrive to writing, or more precisely, did I arrive to writing poetry.

The process of writing multilingual poetry is for me a poetic and linguistic experimentation; a play with language and a language (inter)play. Each of the languages I inhabit has its own timbre, voice, rhythm; it has its own harmonies and melodies, its own colours. Each language mediates my experience(s) of the world differently. This is perhaps why, when I move in a space between languages, I still experience a feeling of loss. At the same time, from this loss, from this lack, comes creativity. It comes in this space of in-between language. This relationship between loss, writing and unwriting is explored in my trilingual poem “Reveries about Language / Sanjarenje o jeziku / Rêveries autour de la langue” as can be seen in the following first stanzas of the three versions:

I traverse the territory of language the way I traverse the desert

Listening to the sounds of silence

Contemplating the void

Searching for the blue, brilliant star

(…)

Prelazim prostranstvom jezika poput šetača koji prolazi kroz pustinju

Osluškujem zvukove tišine

Razmišljam o praznini

U traganju za plavom, blistavom zvijezdom

(…)

Je traverse le territoire de mes langues comme on traverserait un désert,

en écoutant les sons

créés dans le silence,

en quête de l’étoile bleue, brillante (2)

It might seem surprising that I usually begin by writing a poem in English (a language that I acquired much later than my native and mother tongues, Croatian and French). However, writing in English has become natural for me; it is the language I feel closest to, at one level, and one that I feel most comfortable in inhabiting. At the same time, words in English possess very few emotional resonances for me. To compose poetry in a language that has very little or no emotional resonance for me as a writer may sound paradoxical, yet, I have found this lack liberating. My process of writing goes as follows: I first write a poem in English, then I translate it into Croatian and, finally, into French. This process of translation or re-writing, of a constant moving between languages, is quite an interesting one. Only after translating a poem in English into Croatian, am I able to go back to the English ‘original’ to perfect it. Through that process of translation, new echoes, new resonances emerge, rendering the English version more precise, more ‘real’, but also enriched with an emotional layer that I feel was lacking there before I moved to translating it into Croatian. With that also comes the realisation that maintaining the concept of the ‘original’ (language) in the process of translation is an illusion; the concepts of the original and of the translated language become meaningless in the space of the multilingual. Furthermore, the three versions of the poem that I have written become translations of something that does not reside at the level of the linguistic; they become representations, reflections of a non-linguistic form of thought, of a series of images that exist ‘before’ language and that only acquire their meaning and linguistic form in the system of language. During my writing process, I came to another interesting observation. Contrary to what I expected, my relationship to the French language has become more neutral; sounds, images, words and phrases in French have less emotional resonance for me now (although French is my mother tongue or my mother’s tongue), except for a few images, or words, that somehow retained that status. Such is the status of the French word, image and concept of écume motivated, no doubt, by my reading of Boris Vian’s L’écume des jours (1947) that marked me so profoundly in my youth.(3) In the English version of the poem, “Reveries about language”, I write:

My dreams are haunted

by the emotional resonance of words, images

écume

L’écume se languissant

sur les vagues paraît telle une dentelle

fine...

imperceptibly

He stands behind her and touches her naked shoulder almost imperceptibly

(4)

So, while the English word ‘imperceptibly’ - as the words ‘vision’ or ‘feathers’ in the same section - seem to have acquired an emotional value for me in that language, the French word écume has suppressed its English equivalents ,‘froth’ and ‘foam’, in the poem. In the context of the poem, the omission of the English words above marks an empty place; it signifies silence. At the same time, the French word ‘écume’ becomes a prime emotional marker in the poem, through it remaining untranslated into English. This complex process of writing or unwriting in the space of the multilingual can be further unpacked if one compares the English version with the other two versions. In the Croatian and the French versions of the poem, the verses of that section have become enriched with additional layers of meaning and sound, as can be seen in the corresponding verses in Croatian and French:

Emocionalna dimenzija riječi, slika

progoni moje

snove

écume

L’écume se languissant

sur les vagues paraît telle une dentelle

fine...

Morska pjena lijeno se odmara, podrhtava

Na valovima

Poput čipke

imperceptibly

He stands behind her and touches her naked shoulder almost imperceptibly

On stoji iza nje i sasvim lagano dodirne njezino golo rame

(…)

Mes rêves sont hantés

par la résonnance

émotive des mots, des images

écume

L’écume se languissant

sur les vagues paraît telle une dentelle

fine...

imperceptibly

He stands behind her and touches her naked shoulder almost imperceptibly

Il se tient derrière elle et touche son épaule nue presque imperceptiblement

(5)

In the process of translation of the English version of the poem into Croatian and French, words and images in the poem have become more ‘rounded’, more precise; they have acquired emotional resonances and layers of meaning that are present only partially in the English version, I feel. At the same time, the different languages used in the French, and especially in the Croatian version, become traces of each other. They become echoes.

Writing poetry in my three languages is for me a constant experience of identity re-discovery. It is a return to my earlier Selves; a return to my Croatian (but also to my Algerian) roots that I thought I had lost for the most part through the experience of moving out of the country and (involuntarily) suppressing these parts of my identity. My Croatian has always been in competition with my French; when I arrived in Great Britain, I became much more preoccupied with losing my French than with losing my Croatian. Gradually, Croatian took a more prominent position. Paradoxically, I always viewed French as the language of literature and culture, but I also felt a sense of inadequacy in relation to that language. I often feel like I am an intruder in that language. Consequently, I cannot relate the memory of French to my Algerian roots. Yet, some of my earliest childhood memories go back to summers in Algeria. Until I was five, I visited Algeria during the summer with my family. The two main languages spoken were French and Algerian. So, my Algerian experience is accompanied by a complex relationship I hold to French. I remember the intensity of dark red, blue, ochre colours, smells of jasmine and bougainvillea, the garden of orange and lemon trees, my grandmother’s cooking outside and my grandfather’s driving. Yet, I do not relate these experiences to speaking French. Instead, I still hear echoes, traces of sounds in Arabic. Although I do not speak Arabic, it resonates with me; it feels familiar. The missing, the silent language in my poetry, I think, is the Arabic I heard and began to speak as a very young child. It is the language of my Algerian grandparents, my Algerian ancestry tattooed on the back of my memory.

Finally, both as a writer and as a researcher, I am fully conscious of the fact that one can very easily fall into the trap of nostalgia, sentimentality, something that I have always been trying to avoid. All through my adult life I refused to be nostalgic about my Croatian and French/Algerian roots. My multilingual writing experience is teaching me that reviving the sounds, the images, the smells and the colours of my earlier identities and memories through the kind of poetry I am trying to write allows me to tap into parts of my identity that I thought I had lost irrevocably. It is through a much later re-awakening of sensory and sensorial processes of memory recovery that the loss of my Croatian native tongue has became apparent. At the same time, the traces of the Arabic tongue that is part of my Algerian heritage have also resurfaced. These are the parts of Self that I had suppressed, as I was trying not to lose the other equally important part – the French one, whilst also gaining a whole other language - English.

Multilingual poetry allows the reader to move between the words and the worlds of my poems. I am conscious of the fact that most readers do not read, speak and understand the three languages I write in, but I hope that they are able to experience the poems in the space of the multilingual as an invitation to embrace the ‘unfamiliar’ signs on paper through play rather than through fear and uneasiness. This cross—cultural, spatial type of reading may require more openness and concentration, but hopefully, it is also one that is more enriching and thought-provoking.

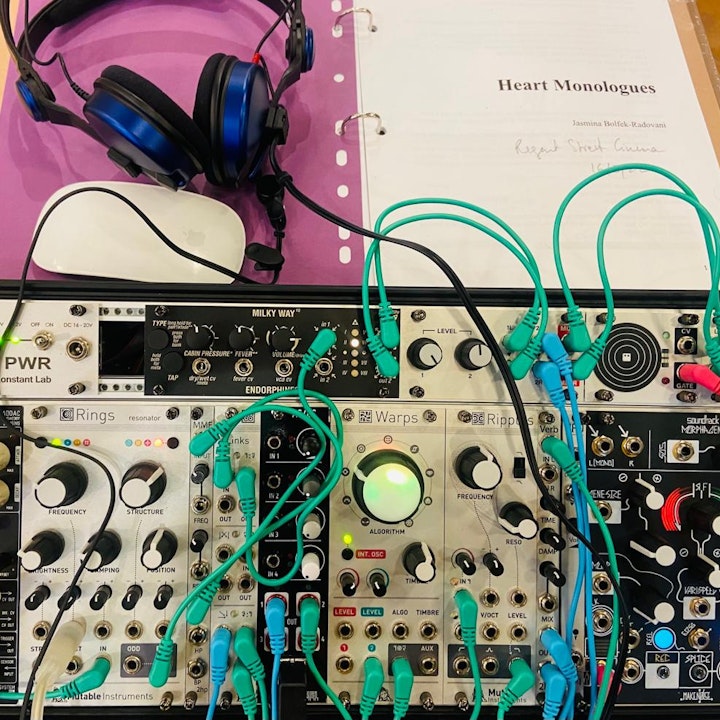

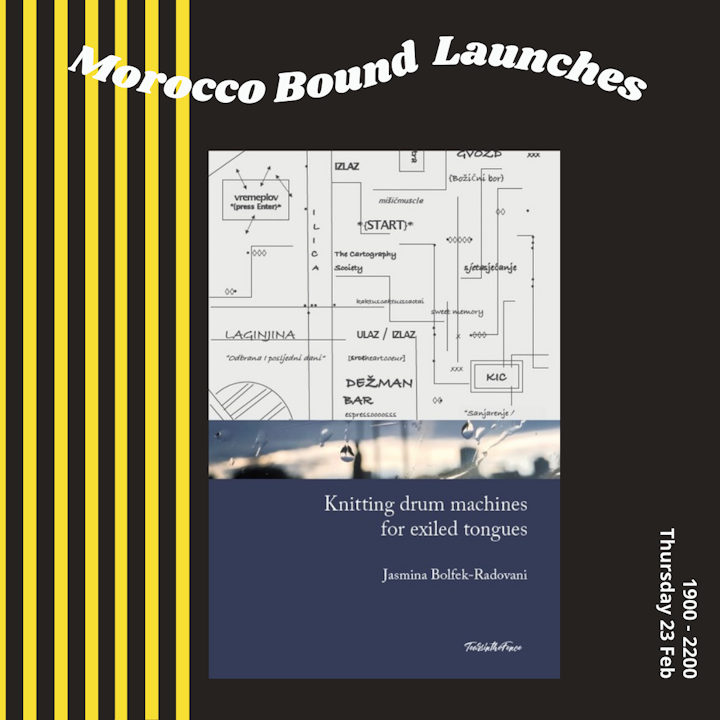

A final word about my multilingual poetry project ‘Unbound’. ‘Unbound’ is a new creative project across UK, Croatia, France and Belgium that explores contemporary poetry writing in the context of multilingualism and across different media. It has been conceived and developed as a result of my own academic and creative journey as both a researcher and published poet of mixed background based in London. ‘Unbound’ aims to challenge the paradigm of monolingual thinking propagated by a variety of public and private discourses formed on the premise of one language, one nation, one identity. It is directly related to my longstanding interest and research on the relationship between language, nation and identity in the postcolonial (Francophone) literary that was part of my PhD work.

‘Unbound’ is imagined as a series of sonic, visual and multilingual ‘promenades’ inviting and inciting the public to immerse themselves fully in the multi-sensorial experience of poetry in English, French and Croatian. It is conceived as a series of evening poetry performances in London, Zagreb, Paris and Brussels. These multi-dimensional – multilingual, multimedia – performances aim to show how the spoken word, sound and image can interact in an innovative way to create a series of ‘unbound’ or free expressions.

Ultimately, ‘Unbound’s’ originality lies primarily in the multilingual exploration of poetry writing. It brings to the fore the idea of the ‘territory’ of language as the only possible space to embrace by any writer working across languages and cultures. It aims to do so in an innovative way, linking multimedia technologies with intimately lived poetic experiences and expressions. It aligns itself with the claim that “poetry is currently the form of writing that is undergoing the most radical regeneration”. ‘Unbound’ aims to bring poetry fully into the twenty first century by engaging the public in an accessible way that will both surprise and delight, but will also be inspiring and thought-provoking.

Footnotes

[1] “Interview with T S Elliot”, in: The Paris Review no. 1., 1959.

[2] Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani, “Reveries about Language, Sanjarenje o jeziku, Rêveries autour de la langue”, in: Still Point Journal, Issue 1, November 2015.

[3] Vian, B., L’écume des jours, Paris: Gallimard, 1947. The first English translation appears in 1967: Froth on the Daydream, London: Rapp & Carol, 1967 (translated by Stanley Chapman). Later translations are: Mood Indigo, NY: Grove Press, 1968 (translated by John Sturrock); Foam of the Daze, NY / Los Angeles: TamTams Books, 2012 (translated by Brian Harper).

[4] Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani, “Reveries about Language, Sanjarenje o jeziku, Rêveries autour de la langue”, 2015.

[5] Idem.