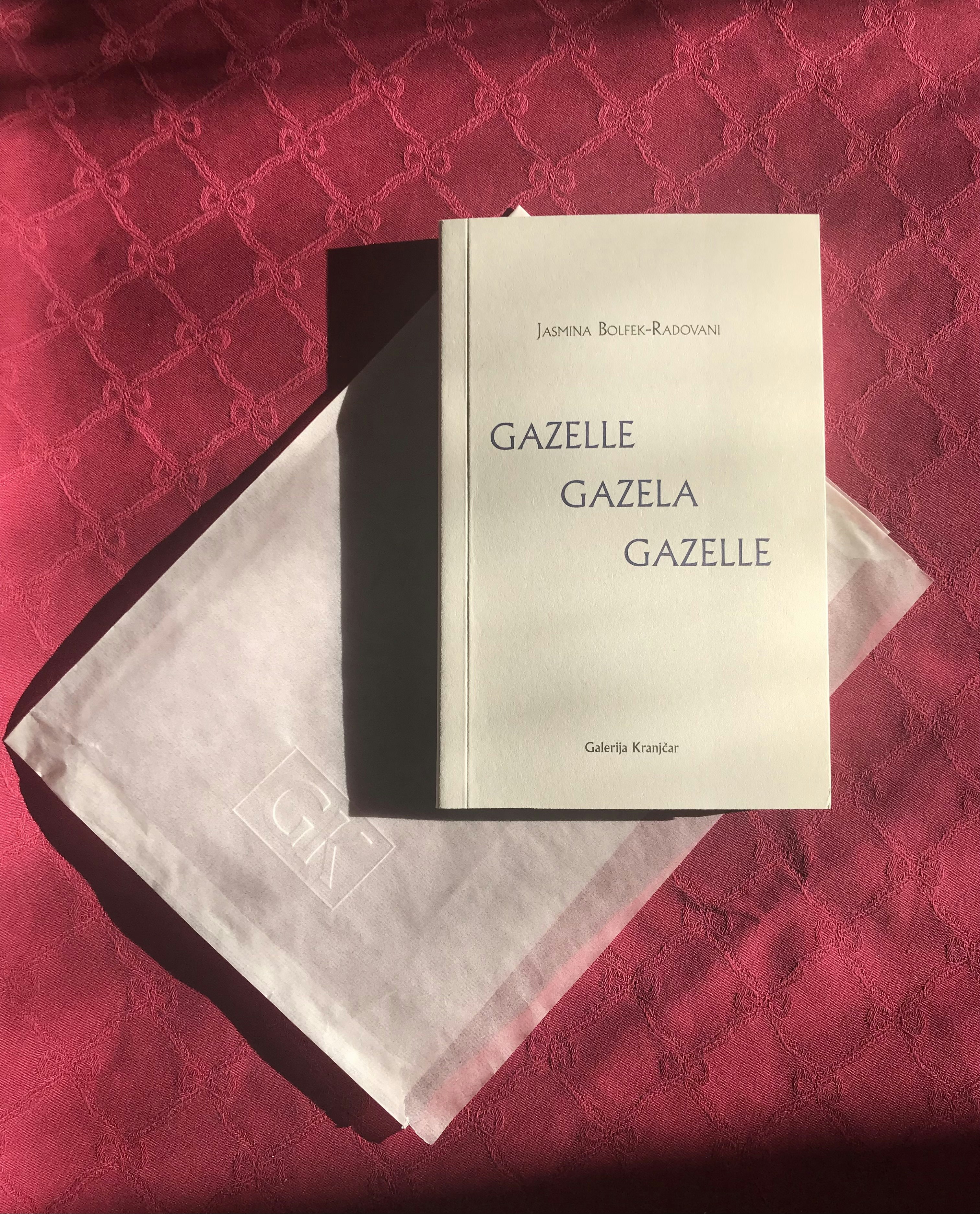

Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani, Gazelle / Gazela / Gazelle, Galerija Kranjčar: Zagreb, 2023.

Birds green trees

In the blue shade, the sun gambols from one wall

To another like a gazelle

The water in the clouds has the unlimited shape of what is left to us

Of the sky.

(Mahmoud Darwish, Under Siege)

Welcome to the Gazelle / Gazela / Gazelle page!

Dobro došli na stranicu Gazelle / Gazela / Gazelle!

Bienvenus sur la page Gazelle / Gazela / Gazelle!

Gazelle / Gazela / Gazelle is the latest multilingual poetry collection in English, French and Croatian by Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani that includes sixty poems inspired by the ghazal poetry tradition. It contains the author's foreword "My arrival at writing: on the (non-)sacrifice of language" in English, French, and Croatian, and nine black and white photographs also by the author.

To order a copy of the book contact kranjcar@kranjcar.hr if you live in Croatia or rest of Europe, or j.bolfekradovani@gmail.com if you live in the UK.

To read the book review "An invitation to share the elegance of the gazelle" (Tears in the Fence, May 2024) by Debra Kelly go here.

Na svjetlosti dana, u sjeni sjećanja: slika, akordi, gazela / In the light of day, in the shadow of memories: image, guitar, gazelle, Zagreb, 1.1.2024

To read the blog piece by Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani on the book launch in Croatian and English here.

Complimentary Materials: Audio, Video

The rose of Algiers (Robert Šantek reads in English)

La rose d'Alger (Pierre Elliot reads in French)

Alžirska ruža (Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani reads in Croatian; camera and editing: Iñigo Berrón; music: Alan Chamberlain)

Some additional poems that have not made it to the Gazelle / Gazela / Gazelle collection:

Perils / Opasnosti (Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani reads in Engl. & Croatian)

In Nevers (Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani reads in Engl, French & Croatian)

The sum of your desires (Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani reads in Engl.)

Paso doble (readers: Pierre Elliot, Robert Šantek, Emily-Céline Thompson)(published in: Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani, Reveries about language / Rêveries autour de la langue / Sanjarenje o jeziku, 2019)

Related essays by the author

"Unbound Lines; Writing in the Space of the Multilingual" , 1 February 2018.

In my grandmother’s Algerian garden / U Alžirskom vrtu moje bake / Dans le patio de ma grand-mère algérienne, 31 May 2018.

Unveiled, Dangerous Women Project, 1 February 2017.

Interviews

Interview in Croatian on Radio Rojc, Višejezični monolozi Jasminina srca, 14 April 2023, Pula.

Background reading: Of gazelles and gazhal poetry

Etymology of the word "gazelle"

From French gazelle, from Old French gazel, from Arabic غَزَال (ḡazāl).

The word "gazelle" in English is derived from the French word gazelle, Old French gazel, probably via Old Spanish gacel, probably from North African pronunciation of Arabic: غزال ġazāl, Maghrebi pronunciation ġazēl. It first came to Europe to Old Spanish and Old French, and then around 1600 the word entered the English language. The Arab people traditionally hunted the gazelle. Later appreciated for its grace, however, it became a symbol most associated in Arabic literature with human female beauty. (Source: Wikipedia).

One of the traditional themes of Arabic love poetry involves comparing the gazelle with the beloved, and linguists theorize ghazal, the word for love poetry in Arabic, is related to the word for gazelle.

Ghazal

The ghazal form is ancient, tracing its origins to 7th-century Arabic poetry. The ghazal spread into the Indian subcontinent in the 12th century due to the influence of Sufi mystics and the courts of the new Islamic Sultanate, and is now most prominently a form of poetry of many languages of South Asia and Turkey.

Originally an Arabic verse form dealing with loss and romantic love, medieval Persian poets embraced the ghazal, eventually making it their own. Consisting of syntactically and grammatically complete couplets, the form also has an intricate rhyme scheme. Each couplet ends on the same word or phrase (the radif), and is preceded by the couplet’s rhyming word (the qafia, which appears twice in the first couplet). The last couplet includes a proper name, often of the poet’s. In the Persian tradition, each couplet was of the same meter and length, and the subject matter included both erotic longing and religious belief or mysticism. English-language poets who have composed in the form include Adrienne Rich, John Hollander, and Agha Shahid Ali; see also Ali’s “Tonight” and Patricia Smith’s “Hip-Hop Ghazal.”

(Source: Poetry Foundation & Wikipedia)

"Gazelle Théorie" & the concept of "gazellage"

Dans Gazelle Théorie je proclame:

Comme il y a des femmes-arbres et des femmes-orbes,

je serai une femme-arabe

je serai une femme-gazelle

une femme goule

une femme avaleuse de silence

a Tunis-Alger-Tripoli-Tanger...

femme-faille, femme-folie, femme-défi. (p. 15)

In her work "Gazelle Théorie" (Pauvert, 2021) the Tunisian writer, poet and translator Ines Orchani gives her review of the history of ghazal poetry, and argues for a feminist interpretation of the metaphor and concept of the gazelle. She dispels the usual clichés associated with women and gazelles as symbols of female beauty and vulnerability and introduces her own concept of "gazellage" defined as the dominant mode of thinking on objectification of women in the Arabic poetry tradition that still permeates the collective imaginary today, thus deconstructing an exotic, reductionist and antifeminist worldview of women.

Interestingly, Orchani begins by saying that the word for gazelle in Arabic is masculine - ghzâl - and later speaks of the multicultural sounds and meanings that the word "gazelle" carries for her in the two languages she speaks - Arabic and French; she introduces the compound "ghzâl-gazelle" thus transcending binary relationships of language, culture, history, memory and identity. She assesses her own internalisation of the binary opposition existing between the two languages and cultures - French and Arabic and continues by saying:

Gzhâl n'a ni sexe ni origine determinés. Ghzâl est un espace. Je le sens en moi, et autour de moi. Dunes. Lumière. Ombres fines. Silhouette en marche... Ghzâl n'a pas de nom, mais s'il fallait lui donner un prénom, je suggère Ryme (terme littéraire pour gazelle) ou Ghozlène (pluriel de gazelle) (p. 31)

Exemples of ghazals: author's selection

Ghazal with Birds

(by Shazea Quraishi)

My beloved is weather, she is cloud, rainshower,

a day downing generous, bright with birds.

Rain is beginning, and rain is ending, longed-for

and sudden, as heavy, as light as birds.

The day brims with possibles, gathered and spilled,

insistent and fleeting as smoke, or the sight of birds.

Streets freshly watered, a telephone line is strung as if pearled, with white after white after white bird.

The breeze brings a name vowen with flowers,

bestows on the trees a blessing, a first light of birds.

Beauty’s a gift, and beauty’s a cage, a thunder of wingbeats, a day and night of birds.

Come to the river, to its bed full of stones, Come rest

on the green of its bank, a delight for birds.

What’s in a name? Ava means voice, melody, song...

so sing! The song is the birthright of birds.

‡

Ghazal of Oranges

(by Jan-Henry Gray)

On New Year’s Eve, my father overfills the baskets with oranges,

mangoes, grapes, grapefruits, other citrus too, but mostly oranges.

The morning of the first, he opens every window to let the new year in.

In Chinatown, red bags sag with mustard greens and mandarin oranges.

A farmer in a fallow season kneels to know the dirt. More silt than soil,

he wipes his brow and mumbles to his dog: time to give up this crop of oranges.

The woman knows she let herself say too much to someone undeserving.

She lays her penance on her sister’s doorstep: a case of expensive oranges.

At the Whitney, I take a photo of a poem in a book behind the glass.

Above it, a painting: smears of blue, Frank O’Hara, his messy oranges.

The handsome server speaks with his hands: Tonight is grilled octopus

with braised fennel and olives, topped with peppercress, cara caras, and blood oranges.

No one at the table looks up, ashamed by the prices on the chic menus.

The busser fills my water and I inhale him: his faraway scent of oranges.

Seventh grade, Southern California: we monitored the daily smog alerts.

Red: stay inside. White: play outside. I forget what warning orange is.

Clutch was serious about art and said our final projects could be

whatever . . . performative . . . like, just show up with a wheelbarrow full of oranges.

Jan, in all of those first six years, why is all you can remember this:

the mist rising in the sunny air as you watched her peeling oranges.

‡

I lost a ghazal; I lost a ghazal

I think I left it on your doorstep...

It’s been a while since I last saw you.

It’s been a while since your lips touched mine.

Like a dancing Sufi, we danced and danced.

We became one, under the ecstasy of ishq.

That night, I lost a ghazal.

I lost the words and the sweetness.

I became the wandering Sufi.

I became the Sufi in your ishq.

My lips are still dripping with your taste,

and I still haven’t found my ghazal...

But I will wonder in your ishq, and I will find the ghazal

which I left on your doorstep, inside me.

(from: “Rooh”, by Rupinder Kaur)

‡

Late Ghazal

(by Adrienne Rich)

Footsole to scalp alive facing the window’s black mirror.

First rains of the winter morning’s smallest hour.

Go back to the ghazal then what will you do there?

Life always pulsed harder than the lines.

Do you remember the strands that ran from eye to eye?

The tongue that reached everywhere, speaking all the parts?

Everything there was cast in an image of desire.

The imagination’s cry is a sexual cry.

I took my body anyplace with me.

In the thickets of abstraction my skin ran with blood.

Life was always stronger . . . the critics couldn’t get it.

Memory says the music always ran ahead of the words.

‡

The Gazelle

Dorcas gazelle

(by Maria Rainer Rilke)

Spellbound creature, can two chiming

words ever achieve the rhyme

which pulses like a portent within you?

Leaf and lyre grow from your head

and all of you moves like a metaphor

through love-songs whose words, soft

as rose petals, settle on the eyes of one

who finishes reading and closes them,

and sees you, transported there, as if

your legs were spring loaded

but holding fire, while your neck lifts

your head to listen - like a girl

pausing while bathing in the forest,

the forest lake in her turned face.

(Translated by Paul Archer; Original: "Die Gazelle")

‡

Ghazal with Eid's ashes

(by Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani)

At the desert border a tent, a dark donkey,

a domesticated gazelle and Eïd’s ashes

Whiteness of sand dunes; the non-place of writing,

trace is erasure is loss; Eïd’s ashes

On the bridge crossing over the Slän River

a doppelgänger hands over Eïd’s ashes

In the story donkeys send political messages,

gazelles rhyme; scattered on black earth Eïd’s ashes

“Call me Eïd” is a sentence in the dream:

reminiscence of the desert: Eïd’s ashes.

Some facts about gazelles

Gazelles are known as swift animals. Some can run at bursts as high as 100 km/h (60 mph) or run at a sustained speed of 50 km/h (30 mph). Gazelles are found mostly in the deserts, grasslands, and savannas of Africa, but they are also found in southwest and central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. They tend to live in herds, and eat fine, easily digestible plants and leaves. Currently, the genus Gazella is widely considered to contain about 10 species. Below are some of them:

The African sand gazelle or Loder's gazelle, is a pale-coated gazelle with long slender horns and well adapted to desert life. It is considered an endangered species because fewer than 2500 are left in the wild. They are found in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and Libya, and possibly Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan.

Arabian gazelles are crepuscular, most active in the early morning and evening when temperatures are cooler. One subspecies is extinct: the Queen of Sheba's gazelle. Most surviving gazelle species are considered threatened to varying degrees.

The Cuvier's gazelle (Algeria, Morocco, Western Sahara, Tunis). Cuvier's gazelle is one of the darkest and smallest of the gazelle species.

The dorcas gazelle (Gazella dorcas), also known as the ariel gazelle, is a small and common gazelle.

The dama gazelle lives in the Sahara desert and the Sahel. This critically endangered species has disappeared from most of its former range due to overhunting and habitat loss, and natural populations only remain in Chad, Mali, and Niger. Unlike many other desert mammals, damas are a diurnal species, meaning they are active during the day.

The rhim gazelle or rhim, also known as the slender-horned gazelle.